At the turn of the 20th century, there were just over 8,000 automobiles in the United States. By 1910 that number had grown to nearly 500,000. Today there are over 285 million motor vehicles on the road.

The transition from the horse-drawn carriage to the automobile is an amazing story that didn’t just happen overnight. By many accounts, it took over fifty years for Americans to replace their trusted horses with new and unfamiliar technology. Horses had been mankind’s dependable transportation for thousands of years, and many Americans believed that automobiles were unsafe.

But our country’s cities were growing, and city planners envisioned a horseless future. Horses required vast amounts of feed, an overnight stable, and then there was the problem of disposing of their copious waste. Automobiles, by comparison, could be fueled with an easily stored liquid energy product called gasoline, could be parked on the street overnight, and their waste products wafted away harmlessly into the air. True, gasoline was poisonous, could be explosive if stored incorrectly, and little was known at the time about pollution; but in spite of these drawbacks, the automobile seemed an attractive alternative to managing millions of pounds of horse manure each day.

The invention of the gasoline-engine automobile is attributed to German Karl Benz, who in 1888 developed the three-wheeled Benz Patent Motorwagen. In 1893, American Charles Duryea began manufacturing standard four-wheeled automobiles that he called the Horseless Carriage. To permanently put the horse out to pasture though, the automobile had to be safe and practical; it had to be something that appealed to Americans and that they could afford to own. Anticipating this need,

Henry Ford designed and built the Model T in Detroit Michigan. The first Model T rolled off the Ford assembly line on October 1, 1908, and the world was forever changed.

Hay to Gasoline - the Changing Energy Marketplace

By the 1920s, horses were a rare sight on the streets of America’s cities, and automobiles had become commonplace. So, too, the gasoline to fuel these automobiles needed to become as ubiquitous as hay. In comparison to hay, however, gasoline was much more difficult to produce and bring to market.

Gasoline had been around since 1859 when Edwin Drake built the first refinery to distill kerosene from Pennsylvania crude oil. Until the advent of the automobile, gasoline was considered a waste product with no practical use. With automobile sales booming in the 1920s, demand for gasoline increased and new

refineries sprang up around the country. Almost one hundred years later, in 2019, there were 135 refineries in the United States producing 389.5 million gallons of gasoline each day.

Refining gasoline from crude oil was only the first step. Gasoline also needed to be safely transported from the refineries to the Americans who wanted to drive their new cars. To accomplish this feat, a network of pipelines to transport, bulk terminals to store, and gasoline stations to dispense needed to be constructed.

With Long Beach, California, in the background, aerial view of oil and gasoline storage and refinery. Photo courtesy of iStock/steinphoto

With Long Beach, California, in the background, aerial view of oil and gasoline storage and refinery. Photo courtesy of iStock/steinphoto

The first gasoline station in the United States was opened in 1905 near St Louis, Missouri. Before filling stations existed, gasoline was sold at pharmacies, blacksmith shops, and hardware and general stores. In 1920 there were about 15,000 gasoline stations in the United States, today there are over 150,000 gasoline stations and around 1,300 gasoline bulk storage terminals across the country.

Booms and Busts

During the latter half of the 20th century, the economy of the United States became increasingly dependent on the free flow of petroleum. This dependence manifested for a number of reasons, but the primary reason is that most Americans thought of automobiles as a necessity for maintaining their standard of living. It should come as no surprise then that America consumes more gasoline per capita than any other country in the world.

Automobile registrations increase over time, eventually matching the population growth trend in the early 1980s. Figure 1 courtesy of FHWA.dot.gov

America’s thirst for gasoline is an economic reality. In general, the relationship between supply and demand governs pricing in commodity markets in all of the world’s economies. In a very simplified sense, the rule is that if demand for something is high and supply is short, the marketplace will quickly push prices higher until an equilibrium is attained. This balancing act between supply and demand is referred to as “elasticity”. Interestingly, crude oil and its products do not follow this economic principle – in fact, crude oil and its products are considered somewhat “inelastic” commodities. Even though prices may change over time, inelastic commodities don’t often reach an equilibrium point between supply and demand. This is true for several reasons, most notably because supply (crude oil production, refining, transportation, and storage) cannot adapt rapidly to major shifts in demand. In the oil business, the seemingly constant surging of supply and demand, and the corresponding wild swings in prices for raw materials and commodities leads to the booms and busts with which the world has become so familiar.

Typically, the oil boom and bust cycle starts when there is abundant crude available for refining into products like gasoline. A steady, reliable supply of crude oil keeps prices low. Low crude oil prices translate into low gasoline prices; and when gasoline prices are low, Americans hit the road. More driving results in an increase in demand for gasoline and a corresponding increase in prices. When prices are high, oil companies have more cash to invest in crude oil production to meet the expected future demand. Unfortunately, when prices get too high motorists reduce consumption, and gasoline demand declines. When demand drops off sharply, prices slump. If prices slump for long enough, crude oil production is cut back.

This cycle has repeated itself numerous times over the decades. From 2010 to 2014 an oil boom resulted in historically high crude prices over $100 per barrel. A bust followed in 2014-2015 when, among other things, U.S. oil production caused a glut in the supply of crude oil.

Weekly average - Oil booms and busts through time. Figure 2 courtesy of econlife.com

Weekly average - Oil booms and busts through time. Figure 2 courtesy of econlife.com

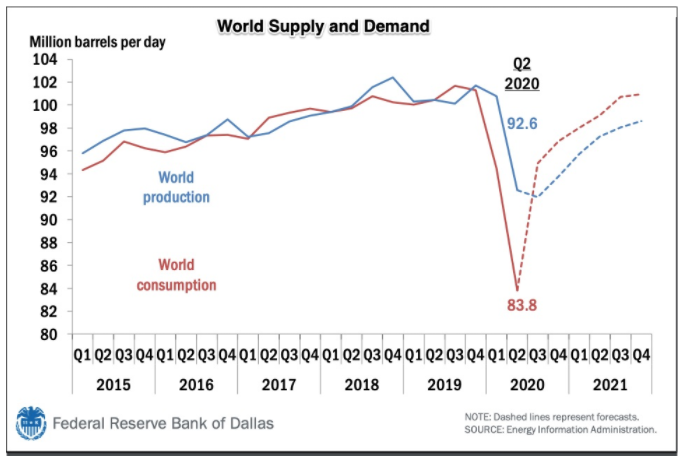

World supply of, and demand for oil. Figure 3 courtesy of econlife.com

Because driving their cars is so important to them, Americans expect their leaders to keep gasoline affordable and plentiful. Those drivers who are old enough to remember it learned a painful lesson during the Arab oil embargo in 1973 when prices skyrocketed and filling stations ran dry. In 2008, motorists did not flinch at price increases until soaring crude prices pushed gasoline prices above $4.00 per gallon.

Oil busts can be caused by either an oversupply of crude oil, a decrease in demand for gasoline, or both. In 2020, the same crude oil supply and demand imbalance that caused the 2014-2016 bust remains relevant. In addition to the global oversupply of crude oil, the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic slashed demand. With renewable fuels and battery and electric vehicle technology rapidly evolving, many believe that demand for gasoline will never return to anywhere near 2019 levels.

Is this the Beginning of the End for Gasoline Demand?

“The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated”.

-Mark Twain

Is history repeating itself? Just as the horse was slowly replaced by the automobile, is the gasoline automobile slowly being replaced by the electric vehicle? Whether the electric vehicle will ever directly replace the gasoline automobile or not is debatable, but along with renewable fuels, electric vehicles will undoubtedly dilute the demand for gasoline over time as fewer and fewer gasoline-fueled automobiles are on the road.

Just as Mark Twain quipped in 1897 from London when his obituary was mistakenly published in the United States, the conventional gasoline-fueled automobile is far from its death bed though. Over the past decades, commodities traders, environmentalists, politicians, and the media have all hypothesized that the United States' seemingly insatiable thirst for oil had peaked and would start to decline substantially over the coming years as oil-replacing technologies became commercially feasible. Each year that analysts predicted oil was dead, Americans surprised them by driving more and consuming more and more gasoline.

Most of the world’s population has become very familiar with gasoline automobiles. Cars are relatively inexpensive to operate and maintain, and gasoline has assuredly become as ubiquitous as hay. By comparison, though, technologies that would replace gasoline automobiles, such as electric vehicles, are still in the relative infancy of development. Electric vehicles use batteries as a source of power. Even though battery technology is evolving quickly, electric vehicles that are comfortable and have good highway driving ranges continue to be novelties for the wealthy, but not practical transportation for the masses.

The transition from the horse-drawn carriage to the automobile took over 50 years. Likewise, it may be decades from today before the gasoline-powered automobile is completely pushed off the road.

This blog post was excerpted from the Terminal of the Future whitepaper.

If you’d like to speak with a specialist about your application or have questions email sales@dixonvalve.com.

Sources:- https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/summary95/

- https://hedgescompany.com/automotive-market-research-statistics/

- auto-mailing-lists-and-marketing/

- http://nautil.us/issue/7/waste/did-cars-save-our-cities-from-horses

- https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/gasoline/history-of-gasoline.php

- https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pnp_cap1_dcu_nus_a.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20150611163521/http://www.nacsonline.com/YourBusiness/FuelsReports/GasPrices_2011/Pages/100PlusYearsGasolineRetailing.aspx

- https://uh.edu/engines//epi975.htm

- https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/tcn_db.pdf

- https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6

- https://www.loc.gov/everyday-mysteries/item/who-invented-the-automobile/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/13/business/energy-environment/oil-prices.html

- https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/prices-and-outlook.php

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-20/the-oil-price-crash-in-one-word-inelasticity

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-09/shale-drillers-are-staring-down-the-barrel-of-worst-oil-bust-yet

- https://econlife.com/2020/07/oil-boom-and-bust-impact/

- https://www.macrotrends.net/2516/wti-crude-oil-prices-10-year-daily-chart

- https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=emm_epm0_pte_nus_dpg&f=m

- https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo