If your business can’t afford to compromise on cleanliness, you’ve likely heard about CIP, otherwise known as Clean-In-Place. Clean-In-Place is a specialized method of sanitizing a manufacturing system’s interior contact surfaces—its valves, pipes, fittings, and tanks—without disassembling equipment.

CIP methods are employed in a variety of industries, from pharmaceuticals to food and beverage to paint and chemicals to personal care products—or in any production environment that demands sanitary conditions.

Clean-In-Place is typically used on components with smooth surfaces, such as tanks, process piping, pumps, valves, and fittings. Some manufacturers rely on COP or Clean-Out-of-Place methods for pieces of equipment that cannot be cleaned in place and must be disassembled.

Compared with full manual or COP cleaning, CIP is less labor intensive; doesn’t require as much production downtime; exposes workers to fewer chemicals; offers results that can be accurately repeated; and can help manage water and chemical costs. Setting up a CIP or COP system can be more expensive initially than cleaning via manual methods, but both are less expensive and time-consuming in the long run.

CIP: A Look Back

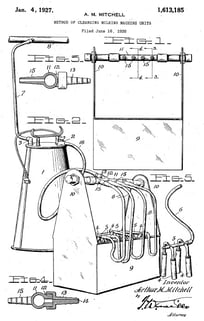

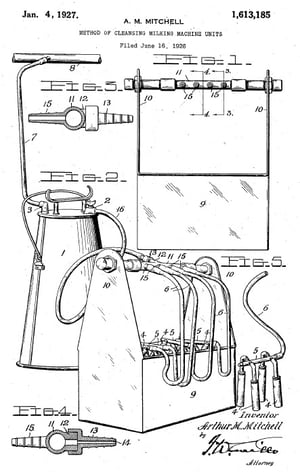

The basic premise behind CIP cleaning is older than you might think. The idea dates to the early 20th century when an American inventor created an automatic washing machine for milking equipment. The primitive device, patented in 1927, involved using a pressurized system to circulate a cleaning solution through hoses and valves, making it possible to scrub four milking machines at the same time.

By the late 1950s, modern-day CIP methods began to emerge in the dairy industry, and by the 1960s, as consumers and the Food and Drug Administration demanded more stringent food safety requirements, the practice became increasingly advanced and spread to additional industries.

The Right TACT

Also, in the late 1950s, the German chemist Dr. Herbert Sinner was developing what became known as the TACT principle. He hypothesized that sanitizing anything relies on four considerations: Time, Action (flow), Chemicals, and Temperature. He compared the idea to using a washing machine to clean clothes at varying temperatures and times using different degrees of agitation and detergents, depending upon the material and amount of dirt on the clothes. He theorized that for effective cleaning, reducing one factor automatically implies strengthening one or more of the others. And conversely: the increase in one of the factors automatically leads to a decrease in one or more other factors. The same idea applies to selecting a CIP system.

CIP operators must consider the right proportions of TACT parameters and what they’re cleaning in order to assemble a system. Different types of food bacteria and chemicals present different types of cleaning challenges. Identifying the kind of product soil you’re cleaning helps identify what you need from a CIP system.

The CIP Process

Most modern-day CIP systems involve a multi-step process. An initial pre-rinse circulates water through equipment via a spray or spray ball to remove surface dirt. Then a detergent is circulated throughout a series of tanks and process lines to kill bacteria and remove chemical residues. The detergent often flows back to a reservoir so it can be reused.

In large CIP systems, the process is run by computer in order to control the velocity, temperature, time, and concentration of chemicals used for sanitizing. A final rinse removes any detergent that remains.

One of the key components in any CIP system is the pump used to propel water and cleaning agents throughout the system. “When you’re sizing a CIP pump, it’s really important that it has the proper performance to enable it to move the CIP fluid at the proper velocity and the proper flow rate,” says Steve Guskey, senior vice president of engineering at Dixon Sanitary.

Guskey says the velocity needs to meet the industry standard of approximately 5 feet per second in order to properly clean components. The larger the line size, the more flow is required to achieve the required velocity. Variables such as internal surface finish, piping elevations, and the number and type of fittings all play a part in the final calculation and equipment specification. And, in order to be cleaned in place, all parts of the processing system must be drainable.

Certification Matters

Almost as soon as the CIP process was invented, users recognized that the method had to be standardized in order to ensure uniform safety and quality control. These standards became known as “3-A standards” for the three interest groups that cooperated to improve equipment design and sanitation—regulatory sanitarians, equipment fabricators, and processors. Today, 3-A Sanitary Standards, Inc. (3-A SSI) is a nonprofit corporation that oversees the 3-A Symbol Authorization program and other voluntary certificates to help affirm the integrity of hygienic processing equipment and systems.

If you run a CIP system, you’ll want it to meet 3-A standards. Dixon Sanitary holds six separate 3-A certifications, earning them through the 3-A Third Party Verification (TPV) program, which requires a professional assessment rather than voluntary compliance. The program ensures that each product conforms in all respects to the published standards.

Dixon Sanitary’s 3-A certifications literally cover thousands of different parts used in the CIP process: valves, hoses, sanitary fittings, filters using single-service filter media, vacuum breakers and check valves, centrifugal and positive rotary pumps, compression-type valves, sight indicators, and more.

Requirements to meet 3-A certification are stringent. Guskey points out that all 3-A certified parts must maintain surface integrity, without pitting, which can cause bacteria to settle and grow. Any plastic gaskets or seals must be FDA compliant, so if a tiny portion breaks off, it won’t harm the consumer. “Each standard has very specific guidelines you have to follow when manufacturing,” says Guskey.

At Dixon Sanitary, those standards are met—at a minimum. “We go above and beyond what’s required by 3-A,” says Guskey. “When we're designing something of our own from scratch, we’re taking the requirements of 3-A and bumping it up a notch.”

For example, he continues, “Maybe on an item, it’s not required to have a leak detection port, but we have one. If something fails inside a valve or pump, you’ll be able to see if it failed. If you don’t have that port, you don’t know. It’s a good, safe feature to have added to a CIP system.”

For more information about Dixon Sanitary CIP products, visit dixonvalve.com or call 800.789.1718 to talk to a specialist.